(Pass)

- 100km

(Pass)

- 100km

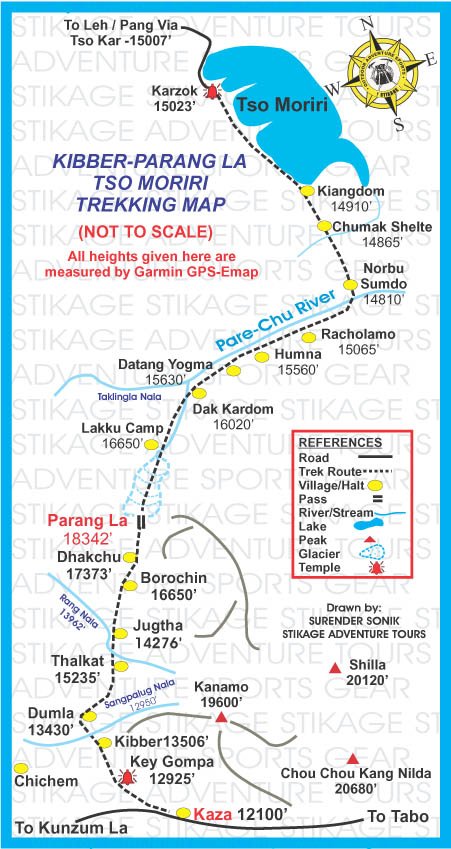

Trek to Tso (Lake) Moriri via Parang La  (Pass)

- 100km

(Pass)

- 100km

To help acclimatisation at still higher altitude ten members of our party headed off by jeep to spend the first night under canvas on the slopes of majestic Chau Chau (6303m) which we approached as the sun set on its western flank. Here at Tashi Gang (4235m) our guide Tomdan and his wife offered us the hospitality of their home for dinner and breakfast.

After breakfast we had some free time to explore this little haven which comprised Tomdan's farm, an ancient small temple and stupas and a herd of Blue Sheep on the other side of the valley.

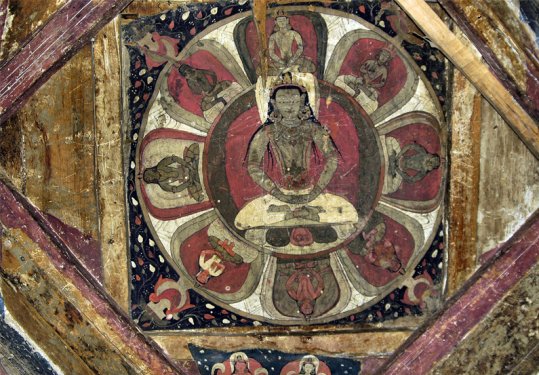

Temple at Tashi Gang Ceiling mural inside temple (All four walls were similarly adorned)

This turned out to be our last leisurely experience of our magnificent surroundings as we set off (on foot from now on) for Kibber (4205m), reputedly the highest settlement in the world to have a motorable road and electricity. Jeep tracks, satellite dishes and the odd tin-roofed government building aside, its smattering of a hundred or so old Spitian houses is very picturesque. Surrounded in summer by lush green barley fields, Kibber also stands at the head of a trail that picks its way north across the mountains, via the high Parang La (5578m) to Ladakh. Before the construction of roads into the Spiti valley, locals used to lead ponies and yaks this way to trade in Leh bazaar (a long way!)

After spending our last night with a roof over our heads we awoke to seventeen donkeys being loaded by twelve porters with sufficient food and fuel for us one way, and return for the porters and donkeys - and we were off! (Map reads from bottom to top)

DAY1: Kibber-Thalkat (Thalta) (4675m) 8h

On this initial stage a height loss of 300m was followed by a re-ascent of nearly 1000m (to 4950m) and then the path fell again for 450m to end up at the glorious situation opposite - amounting to a distance covered of 15km.

DAY 2: Thalkat-Borochin (Boroglen) (5180m) 8h

A rough zigzag rocky path, delicate gravel in places, now descended steeply to the Parilungbi river gorge. This gorge was the cause of the ensuing yo-yo trace of the route which became precipitous and fragile in parts causing problems for horses with unbalanced loads attempting to keep steady on an already narrow track. Our donkeys were much better suited to this terrain. An avalanche bridge was crossed and the river followed upstream for 4 km when then the path began to twist upwards in scree and rocks, then uncomfortable schist debris of an old moraine, past the entrance to a glaciated side valley, and unrelenting to Borochin campground where fresh water and grazing was at a minimum!

DAY 3: Borochin - Parang La (5578m) - Lakku (Kharsa Gongma) (c5050m) 8h

The preceding night was the coldest ever experienced, wrapped in every piece of thermal clothing and feeling claustrophobic and short of breath, to be awoken at 4am to a layer of ice covering the inside of the inner tent. The early start was necessary to traverse the glacier the other side of the pass when the snow was at its optimum condition, to avoid the donkeys slipping on ice or sinking in slush. So up we went in the shadow of the valley, glad to be climbing to keep warm, but with only 50% of the oxygen at sea level more breaths were needed between each step and the heart raced. Our head porter, Tomdan, was to be applauded in dictating the steady pace and frequent halts for us lesser mortals whilst chanting to himself and carrying the teapot! (if you look closely at the left hand of the trailing figure in the right picture below)

Early.......................................................and.....................................................later

Just as the will to live was about to die the cavalry arrived in the form of the Indian army from what we could now see was the top of the pass. After a few questions about what we were doing there (?!) where we were from and going to and a cursory glance at the Inner Line Permits we were allowed to continue the remaining few metres of our ascent - and oh what a vista was displayed as we approached the fluttering prayer flags. These images cannot convey the vast panoramic grandeur of the environment at that point (Parang La 5578m) with 6000m peaks piercing the sky above the snaking Spiti valley far below. The relief and triumph in achieving the highest altitude experienced by any party member was euphoric.

After a frenzied photo-shoot, a cup of chai and a well-earned rest for the donkeys it was necessary to begin the 4km descent over the glacier before the condition of the snow deteriorated.

Us...........................................and...................................Them! (An Austrian party's horses and porters)

Where the Pare Chu outfall developed at the bottom in a jumble of boulders and moraine the growing infant stream was crossed close to where the Pakshi Lamur glacier waters joined from the SE and the trail followed to our next camp at Lakku (Kharsa Gongma) with a splendid outlook on to the ice-cream cone peak of Lakhang (6250m) - just visible on far left of picture below.

DAY 4: Lakku - Dak Kardom (Dutung) (4820m) 5h

A doddle after the previous day's exertions, over shelves and gentle slopes to where the big Takling Nala tributary entered the Pare Chu. The combined streams here attained a width of 2km, overlooked by towering rock faces.

Snow-covered peak of Pari Lungbi (6166m) looking up the valley.........and................................breakfast looking down!

DAY 5: Dutung - Galpa Buze (Before Humna on map) (4620m) 5h

A review of distances between camps resulted in a decision to halt at this enchanting spot where there was grazing for the donkeys and the porters persuaded to upgrade the cold-running water washing facility (river) with hot-pouring (jug over head) from the camp fire. No extra charge. Humour (!) aside it must be stated that the food produced from just a couple of pressure cookers and kerosene burners was wonderful throughout the trek and thoroughly enjoyed by all.

Typical earth formations of the region Galpa Buze

DAY 6: Galpa Buze - Chumak Shelte (Chumik Shaillile) (4540m) 8h

The Pare Chu was followed on the right bank all the way along almost level stretches of stone and sand and several side streams crossed. The landscape on the opposite bank was severe and forbidding until we reached the valley into Ladakh where we had to wade through the river and head north along the dry outflow from Tso Moriri, leaving the Pare Chu to pursue its horseshoe journey east into Tibet and then south back into India to join the Spiti river at Sumdo between Nako and Tabo (villages already visited en route). A short rubble slope was then climbed to the extensive Norbu Sumdo shelf, a plain that is part marshy, part sand like a desert with clumps of vegetation. Ruins of an old fort built by Sennge Namgyal in the seventeenth century were seen and also ruins of an old revenue post set up by the British in the colonial days to collect a head tax of one rupee per family from the Changpas (nomads) and from traders coming over the Parang La from Kaza in Spiti. After lunch we trekked on to Chumik Shaillile, an oasis amid a barren sandy landscape, with the distant Kangri peaks (6666m) shimmering under a cloudless sky.

Lunch at Norbu Sumdo, looking east towards Tibet Chumik Shaillile

DAY 7: Chumik Shaillile - Kele (Halfway between Kiangdom and Karzok on map) (4520m) 8h

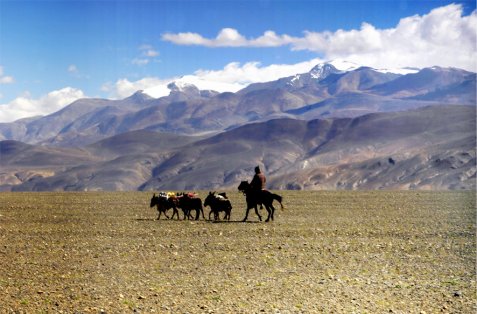

We were now out of step with the original itinerary and so another early start was necessary to reach our revised penultimate destination, but were rewarded by the sighting of Bar-headed Geese and the rare Black-necked Crane. As we headed farther into the Rupshu highland desert a distant gathering sand-storm turned out to be a horseman and donkeys. As he approached our English-speaking porter, Kelsang, recognised him from Chichin - the neighbouring village to our point of departure, Kibber. After an exchange of Tibetan, the rider dismounted to let Kelsang have a ride - a pleasant relief from all the foot-slogging of the past few days.

This provided an opportunity to look back to where we had come from and the second-highest peak in Himachal Pradesh, Gya (6794m), dominated the southern skyline. It marks a tri-junction of Spiti, Ladakh and Tibet. Though shared almost equally by these three bordering areas, it is nearly always described as a mountain found in Spiti. Perhaps a strange perception because on this south side it lies hidden behind a fretwork of ridges and peaks all in a jumble to screen recognition from prying eyes. Consequently it was frequently wrongly identified and "climbed." Eleven years of attempts to climb the correct peak - indeed even to find a way to the foot of it - were largely spent on the Spiti side, out of the Lingti valley and the Chaksachan Lungpa. In these endeavours similarities of the Matterhorn saga of old prevail.

In 1997 an Indian expedition of Everest assault proportions (30 climbers & etc) tried an ascent from the north and returned claiming the summit. This was soon shown to be false, as seen in photographic evidence and from eye-witness accounts. Finally climbed in 1998 by an Indian army team, their reported description was so vague and full of controversial statements that it was disbelieved again by the mountaineering authorities. Only after another Indian team succeeded the following year did the truth emerge with the discovery of a fixed rope, a flag and piton hammered into the highest piece of rock.

Gya is a very difficult mountain to approach from any direction. The best way seems to be from Leh in the north, but getting expedition-size loads there present a number of logistical problems, and moving material down to Chumar via Hanle requires a lot of transportation - latterly with hired horse power. The Spiti ways-in differ in that few problems arise getting stores to Kaza - but onward from there approach distances are greater and a lot of horse and man power is needed to ferry loads to a base camp. Gya climbing potential is considerable, most of the possible-looking major route lines remain to be done.

Continuing north into the Rupshu region of Ladakh we approached the sandy bed of the lake (Tso Moriri) delta-shore, the trail in marsh crossing the often dry outfall of the Phirse Fu and on to the green meadows of Kiangdom. This name is derived from Kiang, the wild ass, even though the animal looked more like a wild horse of the mustang species when viewed through binoculars. At last the idyllic location of the Changpas' temporary settlement of Kele was reached on the shore of Tso Moriri. With the magnificent backdrop of Lungser Kangri I could not imagine a more exotic spot for a welcome "skinny-dip" (with only the donkeys for company!)

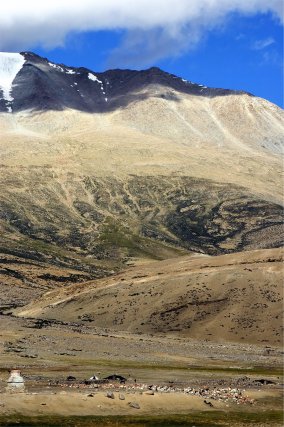

Huge rolling barren hills and fierce winds make Rupshu unlike any other mountain region in the Himalaya. The cold desert-like landscape and vast plains known as Changthang share the area and climate with the adjoining region of Tibet. Rupshu is situated at the south-east end of Ladakh with Tibet to its north and north-east and the Spiti region of Himachal Pradesh to the south. Snow-capped peaks of 6000m rise suddenly from the bleak and mostly uninhabited wilderness. The few occupied small village sites lie between the 4300-4600m and none is below 4000m. With no moisture in the dry air the intensity of the sunrays seems to pierce skin like a laser.

An important feature of this region is its lakes. Centrally situated Tso Moriri is the largest, 28km long, 5-8 km wide and about 150 sq.km in area (but shrinking all the time). Though not a salt-water lake, the water usually remains unfit for drinking (brackish). It is surrounded by peaks reaching 6600m; the Mentok group to the west, Chalung (Kula) in the north, Chamser-Lungser Kangri in the east, and, highest, the Gya group in the south, bordering Spiti. Most of the summits within the ambit of Tso Moriri should qualify as "trekking peaks" on the basis of difficulty, which is objectively nil, but considerations of height with persistent fierce winds may rule out a number of them - those in excess of 6200m.

DAY 8: Kele - Karzok (4527m) 5h

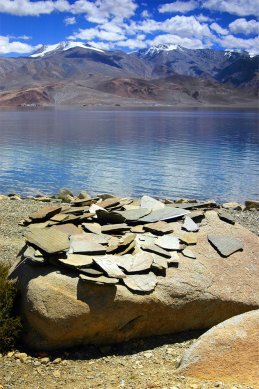

Refreshed by the cool lake water and seeing the end in sight we set off with high spirits on the final leg of the journey, entertained by the Marmots scampering around in the rocks to our left and in awe of the panorama reflected in the lake to our right. As we approached Karzok we passed piles of inscribed tablets of stone (mani), some jumbled, others arranged into a wall which Tibetan culture dictates we pass on the left. Shortly after this some Changpa nomads galloped by, then we were climbing a hill which gave stunning views all round, and finally descended into the village.

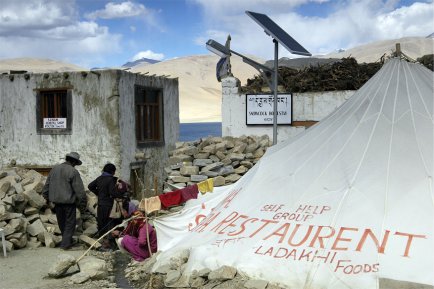

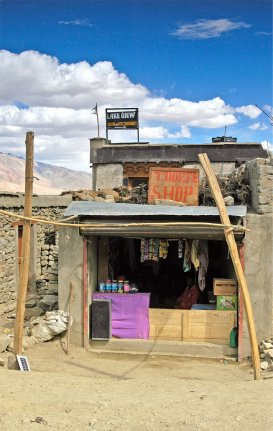

Karzok literally means "middle of the mountains" being the only established village beside the lake and has become an important destination for all visitors to Rupshu. It contains about seventy dwellings, has a few small shops, a simple restaurant and a colony of white tents pitched by a tourist company for the convenience of visitors. "Adobe haciendas" and tents offering accommodation and catering are also springing up out of the rubble. The monastery, which is being renovated, was constructed by contributions from local people and the Changpa nomads. A unique tenancy of this monastery is that it is inhabited only by women. It is said that the original building was put up five hundred years ago by Tsering Tashi Namgyal, a forefather of the present namgyal, and was destroyed by the invading Dogra army in 1833-34.

Karzok had a very "frontier town" feel about it and could imagine "the good, the bad and the ugly" appearing on horseback at any moment! The restaurant not under canvas also had rooms with an electric light which was solar-powered via an accumulator. The switch was twisting two bare-ended wires together - I used a torch! The bathroom was the standard large plastic container of cold water and a jug but the grub was good and they had beer! We spent an enjoyable final evening in the company of our porters, various of whom had to be rounded up from the village hot spots clutching bottles of the local hooch. I found the place fascinating and spent hours absorbing the atmosphere. Mains electricity is imminent and there is a good road and monthly (?) bus service to Leh. Commercial development is only a matter of time. I hope the following images can convey some of the flavour of Karzok.

Prior to our departure for Leh to meet up with our remaining party there was just time for (yes!) another early start to visit the Changpa nomads in the Karzok hinterland. With their families they move from one grazing ground to another with herds of sheep, goats and yaks. They used to live in robos, a tent made of yak wool, which is now being replaced by a sort of conical cotton dwelling.

Changpas are good humoured and cheerful; their lifestyle can be regarded as appalling discomfort and harsh by standards os townsfolk elsewhere in Ladakh, especially in winter. Their concept of economy, way of living, political and religious philosophy is in harmony with the environment. Each family has predertermined and fixed pasture land allotted by Goba, the political chief; this lasts for particular renewable periods. They also have storehouses in Karzok and elsewhere, for food supplies, pashmina wool, etc. Because of severely limited resources, Changpas practice paternal polyandry by which one woman marries several brothers. The brothers' wife and their offspring live together as a complete economic social unit. One or two of the sons, generally the middle son, is dedicated to a monastery to live as a monk, thereby keeping the family resources and social life in balance. As we enter the twenty-first century a number of visitors have commented about the enhanced position of the Changpas with especial reference to wallets bulging with banknotes.

The immensity of the scale of the Himalaya (or the insignificance of man in that environment) can only be brought into perspective by combining the two and there is no better example than that of the Changpa camp at 4600m (just to the right of the stupa bottom left of the image below) with their "cast of a thousand" sheep, goats and yaks. On our way, Graham, our resident ornithological expert, pointed out black redstart, crag martin and Tibetan finch. As well as the black-necked crane and bar-headed geese we had also seen desert wheatear, Kentish plover, yellow-billed chough and Himalayan vulture.

But

now it was time to say goodbye and thanks to our wonderful support team,

especially Tomdan (bottom right) and his son Kelsang (above and to the left) who

now had another eight-day return journey to Spiti.