Karzok - Leh

Just after leaving Karzok by the road above we stopped to show our papers at the Indo-Tibetan Border Post and then headed off on the 221km jeep journey north to Leh. Passing the green-blue Tazang Tso (lake) on our right we climbed steadily to the flattish Namshang La (4845m). Zigzagging for a further 12km we reached the picturesque hamlet of Puga Sumdo where the track west ascended to the Pologongka La (4940m) and became the alternative route to Leh. However our journey took us east to Mahe, but before crossing the new steel bridge over the mighty Indus river (after which the country was named) Inner Line Permits had again to be submitted. Formalities over (again!) we turned northwest to follow the river downstream (its ultimate destination being Karachi) with halts at the hot spring "truck-stop" of Chumathang and the tea-room at Hyamnya (above right). Eventually the colour of the gorge changed and we joined the Manali-Leh highway at Upshi where a final casual scrutiny of our documents paved the way to our ultimate destination.

Mark, Linda, Pat, Julie and Chris went on to visit Manali as we started the trek. Linda writes:

We said goodbye to the Spiti valley at the Kunzom pass, on a bright crisp morning, where we were met by a dazzling array of brightly-coloured flags, flapping against white stupas and a backdrop of snow-capped peaks.

By eleven o'clock our journey had been interrupted and finally halted by a series of landslides completely blocking the road. The first landslide was cleared by a team of travelling workers. We were able to move on after half an hour but two falls of rock then blocked the way. Our jeep drivers were confident two bulldozers at the next village would solve the problem but on finding they were both out of action, set about clearing the rocks by hand.

Three hours later we were on our way again, this time passing through stunning limestone scenery where waterfalls cascaded down the mountain-sides, disappearing under snow to re-appear and plunge into the deep valleys below. The landscape became much greener and wild horses, goats and sheep grazed the high pastures.

At dusk we approached the Rohtang pass. The roadside was covered with many tented retail opportunities (!), now closed for the night. We began our winding descent towards the lights of Manali and finally to the hubbub of the town's lively night life - quite a culture shock after the peace of the Spiti valley!

Meanwhile Caroline had spent a further week in the Spiti valley, and then met up with Pat, Julie and Chris on their return from Manali, at Keylong, to rendezvous with the trekkers at Leh. Unfortunately by then Mark and Linda's holiday was at an end and they returned home via a flight to Delhi.

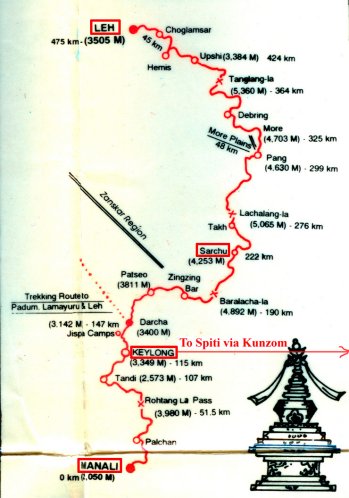

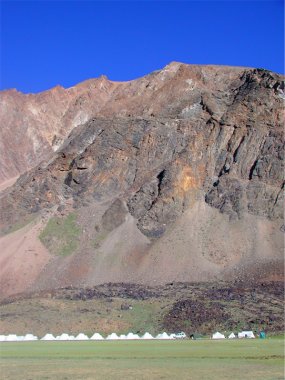

Since it opened to foreign tourists in 1989, the famous Manali-Leh Highway (second-highest road in the world) has deservedly replaced the old Srinigar-Kargil route as the most popular approach to Ladakh, attaining a dizzying altitude of 5360m at the Tanglang La. Its surfaces vary wildly, from bumpy asphalt to dirt tracks sliced by glacial streams, running through a starkly beautiful lunar wilderness peopled only by nomadic shepherds, tar-covered road coolies, and the gloomy soldiers that man the isolated checkpoints. Depending on road conditions, the 485km journey can take anything from 26-30 hours, stopping for a short and chilly night in one of the overpriced tent camps along the route, in their case, Sarchu.

Landslide on the Kunzom-Keylong road

Keylong and potato fields Stupas at the Kunzom Pass Tent camp at Sarchu

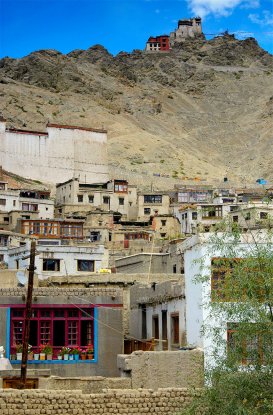

Approaching Leh (right) via the sloping sweep of dust and pebbles that divide it from the floor of the Indus valley one can have little difficulty imagining how the old trans-Himalayan traders must have felt as they plodded in on the caravan routes from Tibet: a mixture of relief at having crossed the mountains in one piece, and anticipation of a relaxing spell in one of central Asia's most scenic and atmospheric towns. Spilling out of a side valley that tapers north towards eroded snow-capped peaks, the Ladakhi capital sprawls from the foot of a ruined Tibetan-styled palace - a maze of mud-brick and concrete flanked on one side by cream-coloured desert, and on the other by a swathe of lush irrigated farmland. After settling into the hotel and experiencing the joys of a hot shower (and flush toilet!) we met up with the rest of the party who had either spent extra time in the Spiti valley or Manali.

The view (left) from the hotel roof was spectacular, with Namgyal Tsemo gompa perched precariously on the shaly crag above the palace, which Caroline and I attacked the following morning. The above image was taken from the gompa with the white Shanti Stupa visible on the distant hillside. Inaugurated in 1983 by the Dalai Lama, the "Peace Pagoda", whose sides are decorated with gilt panels depicting episodes from the life of the Buddha, is one of several such monuments erected around India by a "Peace Sect" of Japanese Buddhists. We ascended by the "north face!" to the twin "Peaks of Victory" connected by giant strings of multicoloured prayer flags. As we set off mid-morning we had to be content with the view from the gompa as it is only open 7-9am, but that was enough.

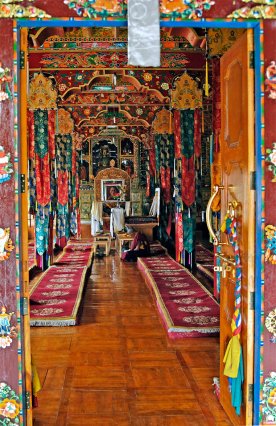

Descending by the the southern slope we came across the red-painted Maitreya temple. Thought to date from the fourteenth century, the shrine houses a giant Buddha statue flanked by bodhisattvas (below)

The palace (above) of the sixteenth-century ruler Sengge Namgyal was on a similar level to the temple. A scaled-down version of the Potala in Lhasa, it is a textbook example of medieval Tibetan architecture, with gigantic sloping buttress walls and projecting wooden balconies that tower nine stories above the surrounding houses. Since the Ladakhi royal family left the palace in the 1940s, damaged inflicted by nineteenth-century Kashmiri cannons has caused large chunks of it to collapse but is now undergoing restoration.

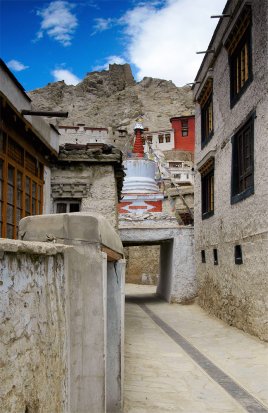

The track back to our hotel led us through the old town. Apart from the odd electric cable, nothing much has changed here since the warren of flat-roofed houses, crumbling chortens, mani walls and narrow sandy streets was laid down in the sixteenth century.

Ladakh's most photographed and architecturally impressive gompa is at Tikse, 19km southeast of Leh. Founded in the fifteenth century, its whitewashed chortens and cubic monks' quarters rise in ranks up the sides of a craggy sun-bleached bluff, crowned by an imposing ochre- and red-painted temple complex whose gleaming golden finials are visible for miles in every direction.

One of the highlights of the visit was the view from its lofty roof terrace. A patchwork of barley fields stretched across the floor of the Indus valley, fringed by rippling snow-flecked desert mountains and a string of Tolkienesque monasteries, palaces, and Ladakhi villages: Shey and Stok to the northwest and Matho on the far side of the river.

The income generated by Tikse's reincarnation as a major tourist attraction has enabled the monks to invest in major refurbishments, among them the new Maitreya temple immediately above the main courtyard. Inaugurated in 1980 by the Dalai Lama, the spacious shrine is built around a gigantic 14m-high gold-faced Buddha-to-come, seated not on a throne as is normally the case, but in the lotus position. The bright murals on the wall behind, painted by monks from Lingshet gompa in Zanskar, depict scenes from Maitreya's life.

The following day was our last in this exotic environment and was spent soaking up the atmosphere of the bazaar. Sixty or so years ago, this bustling tree-lined boulevard was the busiest market between Yarkhand and Kashmir. Merchants from Srinigar and the Punjab would gather to barter for pashmina wool brought down by nomadic herdsmen from western Tibet, or for raw silk hauled across the Karakorams on Bactrian camels. These days, though the street was awash with kitsch curio shops and handicraft emporiums, it retained a distinctly central Asian feel. Clean-shaven Ladakhi lamas in sneakers and shades rubbed shoulders with half-bearded Baltis from the Karakoram and elderly Tibetan refugees whirring prayer wheels, while now and again, snatches of Chinese music crackled out of the shopkeepers' radios. Bright pink, turquoise, and wine-red silk cummerbunds hung in the windows. Inside, sacks of aromatic spices, dried pulses, herbs and tea were stacked beside boxes of incense, soap and spare parts for kerosene stoves. At the bottom of the bazaar, women from nearby villages, stovepipe hats perched jauntily on their heads, sat behind piles of vegetables, spinning wool and chatting as they appraised the passers-by. But genuine product could be found with a little perseverance and some sequinned cushion-covers made from traditional embroided Indian patchwork, and a cotton shirt and wool jumper proved useful souvenirs.

The next morning we all flew from Leh to Delhi where the last night was spent in a quiet residential quarter before returning home the following day from "the journey of a lifetime"